Syracuse Police Chief Frank Fowler drives through Canfield Green Apartments, where in 2014 Michael Brown Jr. was shot and killed by Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson.

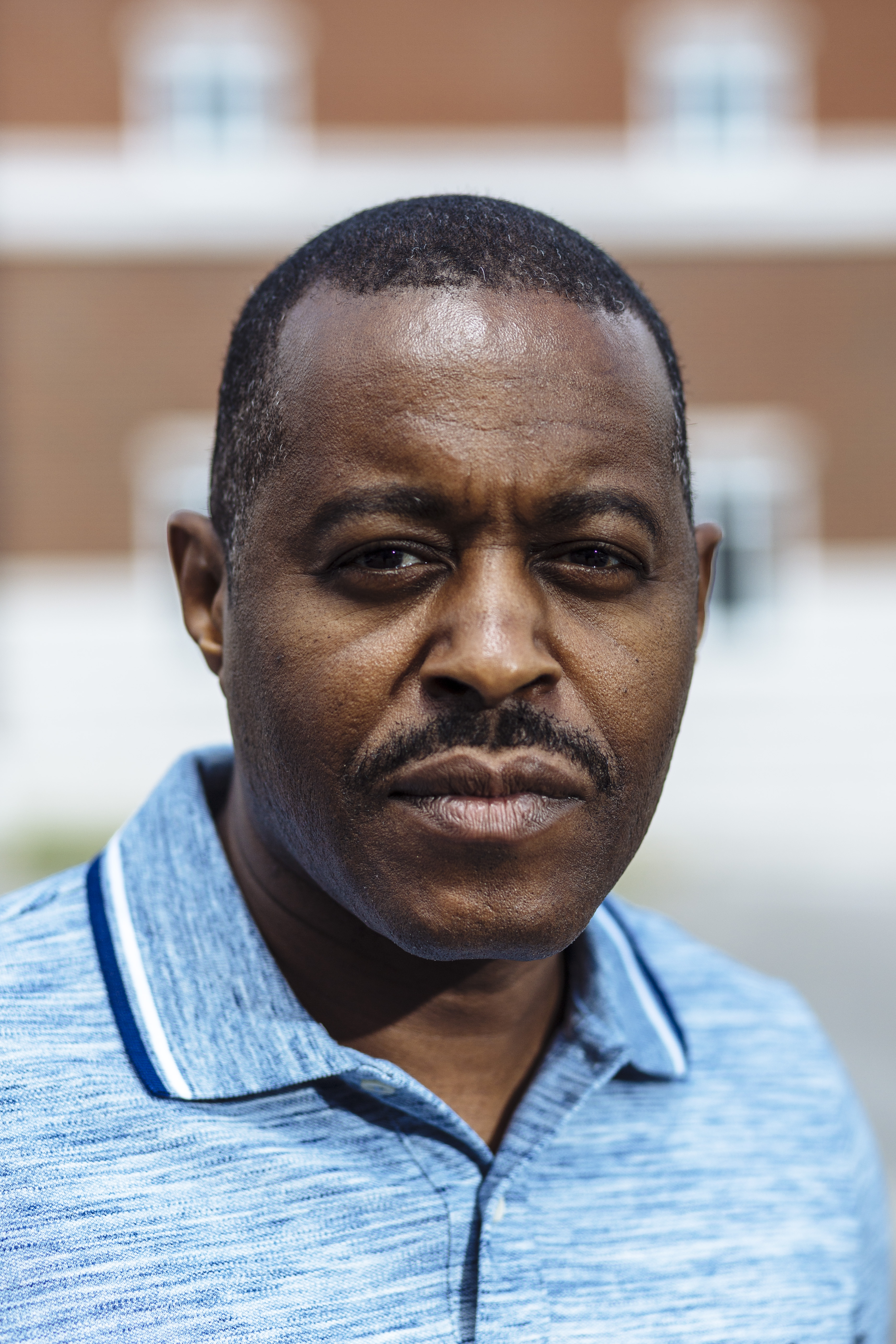

Chief Frank Fowler made it out of the community where Michael Brown died

As a youngster he accepted the cops might shoot him — and one day they almost did

written by:

Justin Mattingly

photography by:

Michael Santiago

ALSO FIND:

> Meet the Ferguson Police Chief

> List of Syracuse crime statistics

KINLOCH, Mo. — A 19-year-old Frank Fowler woke up on a summer morning in his small room in his family’s small apartment and approached a big dresser with a big mirror.

He’d been living day-by-day, facing the challenges of growing up in an urban city that’s a 20-minute drive from downtown St. Louis.

“The minute you walk out that door in the summertime and the sun hits your face, it’s like ‘What’s next?’ What’s around the corner?” Fowler says now. “And it keeps coming and coming and coming and then at night, if you’re fortunate enough to lay down at night to get some sleep, you know that tomorrow you start it all over again.”

As he approached the mirror on this morning, he saw a short black teenager with long hair and bold brown eyes. He looked into those eyes and asked himself a simple question: “What was the best thing and the worst thing that could happen to me today?”

The answer to both was the same: Die.

“I wasn’t suicidal. I didn’t have a death wish,” Fowler says now. “I didn’t want to die. But if I did die, it was over. I wouldn’t have to carry this anymore.”

Thirty-five years later, Fowler has traded the burden of urban street life for a different challenge as Syracuse’s police chief. Fowler, who is set to retire at the end of 2017, still holds those memories and experiences close to him. They’ve shaped the way he patrolled the streets of Syracuse as an officer and now in his role as the top man of a police force tasked with protecting more than 144,000 people.

“He looks at the whole community. He can relate to the people in the community,” said New York state Assemblywoman Pamela Hunter. “He’s the ‘People’s Police Officer.’”

“He looks at the whole community. He can relate to the people in the community,” said New York state Assemblywoman Pamela Hunter. “He’s the ‘People’s Police Officer.’”

“One of the biggest mistakes that an officer of color can make is to come into the system and assume they have to assimilate. I’ve been told a lot of things on this job about what to expect, what to do and how to conduct yourself in certain situations. No one has ever told me to compromise my principles and who I am as a human being in order to be effective at doing this job.”

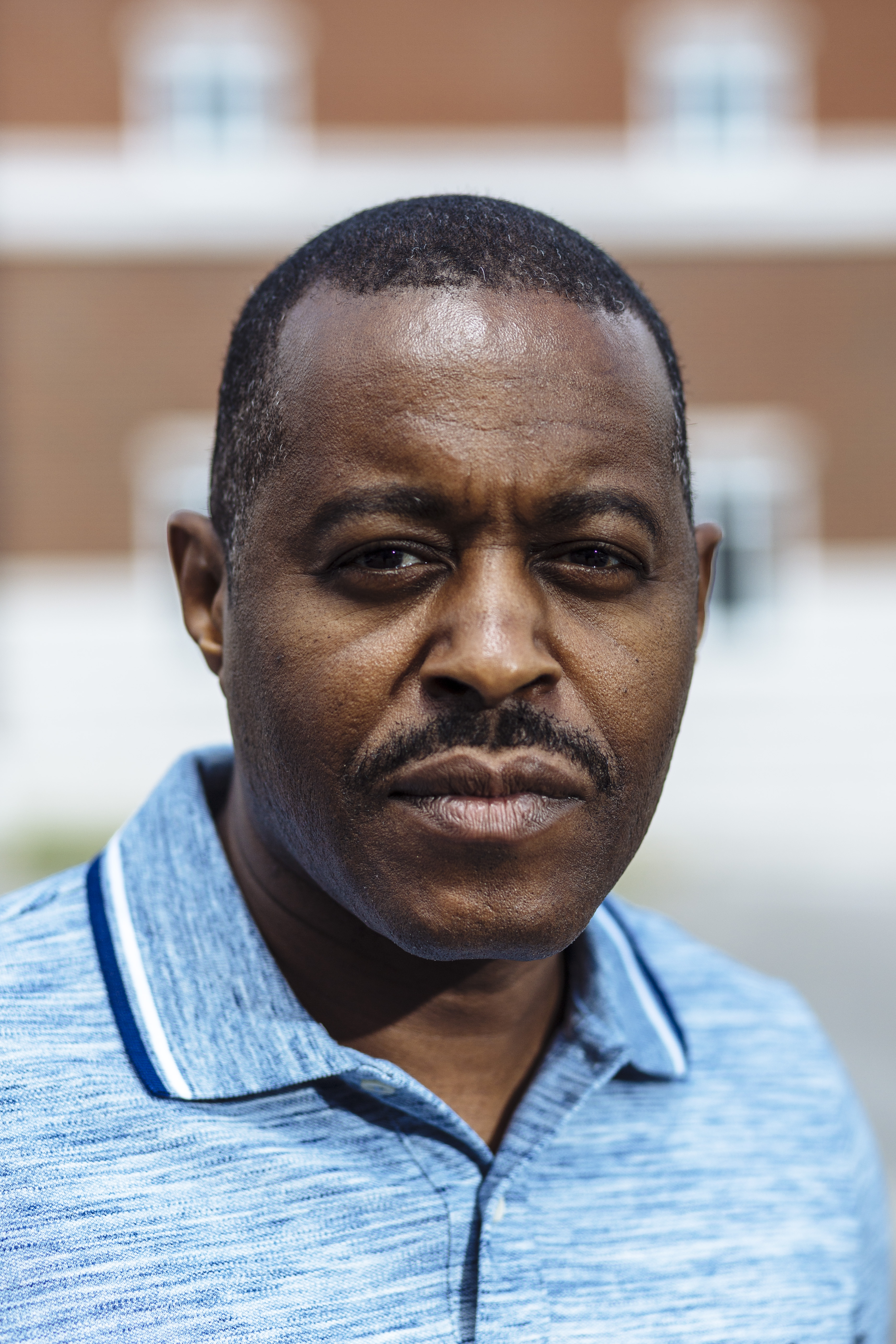

caption here.

“Sir, I’m a kid”

Six years before Fowler had reflected that the best thing that could happen to him was to die, he thought that indeed might happen at the hands of St. Louis police.

Fowler and some of his friends were playing stickball in the narrow parking lot of what is now the Martin Luther King Community Center in the central west end of St. Louis when “Clarence,” a teenager roughly Fowler’s age, “had to get touched” for snitching on Fowler.

The rules of the street required it, Fowler said, and so the 13-year-old punched the bigger Clarence as payback. A short time later, Clarence appeared again. This time with backup: the police.

On a visit back home this spring, Fowler said he still remembers exactly how the situation played out. He pointed out where the key players stood that very day.

A white police officer got out of the patrol car with Clarence and walked across the street to confront the group of boys, Fowler included, who remained in the parking lot. A fence separating them, the officer pointed at each boy and said “You come here.” They all played the ignorance card but when the officer got to him, Fowler knew that wouldn’t work.

Young Fowler approached the fence before the officer grabbed him by the shirt with his left hand and drew his gun with his right.

“Anything you think you shouldn’t say to a kid, he says it,” Fowler recalls.

He’d seen people die and realized that the rules of the street, the same ones that governed his retaliation when Clarence snitched, said that if you pull a gun you better use it.

Fowler’s life was before his eyes. The only words he could muster came out: “Sir, I’m a kid.” He repeated the phrase over and over again until the officer released him.

“I don’t know what he saw in me. The only thing I know is that when he pulled that gun on me, I was like ‘holy sh*t, I’m about to die,’” Fowler said. “There have only been a few times in my life when I thought death was imminent and that was one of them.”

Growing up in St. Louis county — most of it in the city itself — there was a negative connotation when it came to police, Fowler said. As he reluctantly turned around, fearing his friends had heard his helpless plea that day, he realized that they “were just as shook as I was.”

Fowler’s able to laugh about the moment now — he’s always had the “gift of gab” — standing in the exact space where he thought he’d die. Given that a near-death experience was his first true memory of police, Fowler’s still amazed that he ended up in law enforcement.

Kinloch, the oldest African-American community in St. Louis, was once a flourishing city. It was one of the first suburbs in St.Louis that experienced white flight once the first black families moved into the area. St. Louis began to buy up property from its residents for an expansion of the airport in the early '80s that's never happened. The city now is mostly vacant with few homes, yet all churches remain.

"I don’t know what he saw in me. The only thing I know is that when he pulled that gun on me, I was like ‘holy sh*t, I’m about to die.' There have only been a few times in my life when I thought death was imminent and that was one of them,” Fowler recalls at the location where, in his youth, a cop pointed a gun at him.

Frank Fowler was born in Kinloch, Missouri, a city that borders Ferguson. That's where Michael Brown Jr. was shot and killed by a Ferguson police officer. Today Fowler credits his upbringing there for shaping his career in law enforcement. "I believe that effective change has to start from within,” he said. “Whether it’s within a person or whether it’s within an institution, in order to have effective change, it has to start from within. Because it’s only from within that you have influence.”

“There’s nothing here”

Fowler, dressed in a gray suit with a purple tie, is driving around his gutted hometown of Kinloch when he gets a call from one of his eight older sisters.

“I’m riding around through depressing Kinloch,” he tells her. “There’s nothing here. Nothing.”

The city used to be a residential area with working-class apartments for labor workers like Fowler’s father. It’s now a ghost town in shambles with a population of a mere 299 people after losing more than 80 percent of its population between 1990 and 2000 because of an FAA noise-abatement program for the St. Louis airport.

Along a side street, wheels, brush and glass litter the middle of the road. A few churches still call Kinloch home but local business is all but gone.

“I knew it was bad but this is even worse than I thought it was,” Fowler said while driving. “This is like a foreign place to me.”

Fowler takes a right hand turn and smiles as he sees the most sacred area of his childhood: Kinloch Park.

The park is one of the few areas of the deserted city that remains the same as when Fowler used to frequent the basketball courts and baseball field. Standing at center court of the “good players” court, Fowler recounts the festivals, intense pickup games and old men gambling up in the gazebo. He tells stories of his cousin, who was shot and killed in St. Louis in a dispute over a girl, playing on the court.

When he was 16 years old, Fowler was walking to the court when a homeless man on one of the park’s two picnic tables stopped him. His question: Why did the teenagers consistently called each other n***** when they played?

“Do you think that’s a bad word?” the homeless man asked. Fowler said “No.”

“Well what if a white person called you that?” Fowler insisted the man didn’t know what he was talking about and walked away. He got about halfway to the court when, he said, he realized the homeless man was right.

“From that day on I’ve never used that word. It hasn’t crossed my lips since that day,” Fowler said.

Much of the swearing came on the court during the pickup games. Fowler, an amateur boxer growing up, came up with a solution to defuse tensions: When players were getting into it during a game, they’d stop play to form a circle at the blue-colored center court. The trash-talking players would box in the circle.

“If you couldn’t box, you kept your mouth shut,” Fowler jokes. “You couldn’t run. You were going to catch some leather.”

One of the first acts of community policing Fowler saw was in that man-made boxing circle.

Two police officers, one white and one black, walked by the court. Police officers weren’t friendly with him when he was growing up, Fowler said.

“I grew up being black. I understood fully what that meant from an urban cultural perspective,” he said. “I’m honest with myself. I’m not going to bullsh*t myself. I know what all that means.”

“I grew up being black. I understood fully what that meant from an urban cultural perspective,” he said. “I’m honest with myself. I’m not going to bullsh*t myself. I know what all that means.”

The white officer started talking back to the players on the court when one of Fowler’s friends offered up: “If you didn’t have the badge and the gun …. ” to which the officer responded, “Well this badge and the gun come off.”

The neighborhood boys formed their routine circle in which the white officer, who turned out to be a former boxer for a local club, won the fight against one of the teens. The circle-creators went crazy in excitement.

Syracuse Police Chief Frank Fowler, looks on at the vacant and boarded up apartment complex where he and his family used to live in Kinloch. Growing up, Fowler moved a lot and lived in many different places throughout St. Louis but has fond memories of his time in Kinloch, a city that borders Ferguson, MO.

“Has to start from within”

Becoming a police officer wasn’t exactly the plan for Fowler — it was more an accident.

Shortly after looking himself in the mirror in the family apartment on what is now Rev. Dr. Earl Miller Street, Fowler realized he needed to leave his dead-end job at a rental company that rented out party supplies and hospice equipment. He was driving home from work one day when he saw an Army recruitment sign.

Fowler stopped at the local recruitment center and passed the exams, inspired after the recruiter told him he’d fail as a tactic to spur him on. Fowler saw in Army-distributed material that members of the transportation unit of the Army often ended up in Hawaii, so he joined the military. He’s still never been.

Instead, the Army took him to Europe, the Middle East and Panama, with domestic stations at Fort Dix in New Jersey and Fort Drum, an hour’s drive north from Syracuse and where he’d eventually exit the military.

He was watching television one night when he saw a non-fatal stabbing on the Syracuse news. That stabbing would have been so inconsequential it wouldn’t have made the news back home, Fowler said, so he thought the city would be a safe place to live for him and his wife, whom he met at Fort Drum.

While working in Syracuse, Fowler saw a recruitment pitch for the police department. He went to a police recruiter and filled out the form to apply as a joke for when he returned home on a visit to St. Louis, given his past experiences with cops.

But his competitive instincts took over. He got a call saying he’d passed the test — and he saw an opportunity to have an impact.

“I believe that effective change has to start from within,” Fowler said. “Whether it’s within a person or whether it’s within an institution, in order to have effective change, it has to start from within because it’s only from within that you have influence.”

“I believe that effective change has to start from within,” Fowler said. “Whether it’s within a person or whether it’s within an institution, in order to have effective change, it has to start from within because it’s only from within that you have influence.”

On a sunny March day working as a counselor at the Elmcrest Children's Center, he got the notification that he had been accepted into the police academy.

“A person like me becoming a police officer? How does that happen?” Fowler asked.

That same feeling came over Fowler 20 years later in 2009 when he received a phone call from Syracuse Mayor-elect Stephanie Miner. He had reapplied for his position as deputy chief of the police department’s Community Services Bureau, but the call was for a different position: chief of police.

“You messing with me?” he asked her on the phone. “I never envisioned myself being the chief of police, but sure. I can do the job.”

He jokes that he’s still surprised she chose him. Miner’s press secretary did not respond to multiple requests for an interview for this story.

“Some people say life being hard in the hood is an exaggeration. They don’t know what they’re talking about. It’s exhausting to navigate the hood each and every day and all the different dynamics that are associated with it.” Chief Fowler joined the military knowing it was something that he needed to do. While stationed in Fort Drum, he applied to become a Syracuse Police officer and quickly rose in the ranks and would become police chief in 2009 after accepting the position that newly elected Mayor Stephanie Miner offered him.

Paintings of prominent black St. Louis politicians, entrepreneurs and entertainers decorate boarded-up doors and windows of blighted buildings. Artist Christopher Green was commissioned by St. Louis nonprofit Better Family Life to paint the portraits for the organization's Beyond the Walls project, to help bring beauty and inspiration to the city.

“Had to do something different”

Suburban Avenue, a two-lane road with little traffic, connects the city of Kinloch to the city of Ferguson. Kinloch had always been the more residential area before its population dissolved, while Ferguson was the more developed town with businesses and a larger population.

As Fowler drives around Ferguson on the recent visit, he relates locations and businesses back to the shooting of Michael Brown about three years ago.

Brown — an 18-year-old, unarmed black teenager — was shot six times and killed by a white police officer Aug. 9, 2014. Brown’s body laid in the street for four hours after the shooting, which took place shortly after Brown had taken cigarillos from a convenience store and assaulted a store clerk.

After the Brown shooting, thousands of community members — some from Ferguson, others from outside — crowded the streets to protest. The story made international news when the protests turned violent. Protesters threw Molotov cocktails at police, who fired tear gas and rubber bullets back and brought in military-style vehicles.

A jury decided not to charge Officer Darren Wilson, the officer who shot Brown, in November 2014. Protests following the jury’s decision spread from Ferguson across the U.S.

Fowler, driving on Canfield Drive, the road where Brown was killed, recalls going into Syracuse Deputy Police Chief Shawn Broton’s office to tell him that things were going to “get crazy” after police officials in Ferguson revealed what they said were the facts of the case, portraying the police as innocent while still assuring an investigation into the shooting.

“I had no idea it was going to turn out like it turned out,” Fowler said.

When a Syracuse police officer shot and killed a citizen on Father’s Day last year, Fowler knew he’d have to react differently than the way his police peers in Ferguson had handled the Brown shooting and subsequent riots.

On Sunday, June 19, a group of more than 300 people were partying in the James Geddes housing complex when gunfire and fighting erupted. SPD officer Kelsey Francemone responded to the chaotic scene and said she saw Gary Porter, 41, fire a handgun. Francemone shot and killed Porter, and in turn was attacked by people in the crowd. An investigation did confirm Porter was armed, after many in the crowd said he was not, and tensions simmered. Francemone was cleared of wrongdoing by a grand jury in August.

After the shooting, the question hung over Syracuse: Would it be “another Ferguson?”

After the shooting, the question hung over Syracuse: Would it be “another Ferguson?”

Fowler reacts to police shooting videos with a “here we go again” mentality. Everyone wants to have a video go viral, he said.

“If you only introduce the sensational part and leave the rest for interpretation, that’s when there’s going to be a lot of discussion generated,” he said.

Fowler tried to encourage patience until all the details of the shooting were released and waited a few days before releasing surveillance footage showing the chaotic shooting scene. He limited police presence at protests and rallies, to avoid generating even more anger. Instead he had officers ready to be dispatched from headquarters if they were needed. All the protests regarding the shooting ended peacefully.

“I know how the crowd thinks. I have the luxury of thinking like the crowd and I have the luxury of thinking like the police. I know that pain. I’m very familiar with displaced anger. I know you look for the biggest target you can attack,” Fowler said. “Ferguson, Baltimore, they provided a blueprint for how you behave during these riots and it wasn’t healthy. In order for you to avoid that, you had to do something different.”

The challenges

There have been challenging cases throughout Fowler’s eight years as chief and 28 with the police department. The father of three considers the case of Maddox Lawrence, a 21-month-old baby who was killed by her father last year, one of the toughest during his time as chief along with the drive-by shooting that killed 20-month-old Rashaad Walker Jr.

The challenges, though, extend beyond the cases. There are diversity problems, budget issues and high crime rates that linger.

When Fowler started as chief, he inherited a force that was 94 percent white. In SPD’s 2011 report, the department called its “greatest deficiency” its inability to recruit black officers.

“If you have a police department that’s reflective of the people they serve, the community is going to say that department truly represents them,” Fowler said.

The number of white officers today is just barely under 90 percent, according to SPD’s 2016 report, with the count of black officers at 7.1 percent.

“When you’ve lived in a neighborhood or have connections to a neighborhood, people know that. It makes a big difference to people,” Fowler said. “That doesn’t mean that you can’t do the job if you live somewhere else, I think that because you live in the community, it makes your ability to do the job that much better.”

SPD is in good shape with talent, Fowler said, but it’s not when it comes to numbers, down 31 police officers overall.

The police department’s budget has been a point of contention during city budget talks, with the Common Council approving a budget that cut $1 million from SPD’s overtime budget.

Miner and Fowler quickly came out against the approved budget, which Miner has since vetoed. Council wanted to have a new class of 31 recruits to fill the empty spots on the police roster. The department added 25 last year after 36 officers retired.

"The thought of having a class of new recruits is very attractive. However, to do so at the expense of cutting our overtime budget would have a crippling effect on our current operations," Fowler said. "Each year, the calls and the demand for police services increases. Our only way of meeting these high demands is through the use of overtime."

Of the high crime rates in Syracuse, the one that gains the most notoriety is the number of homicides. In 2016, 31 homicides were reported in the city, up from 23 the year before.

Fowler’s son, Frank Fowler Jr., 25, has been arrested multiple times, including July 2016 on felony drug charges. The charges were later reduced to misdemeanor charges.

CRIME STATS IN SYRACUSE

Burglaries

2016: 1,030

2015: 1,222

2014: 1,458

2013: 1,809

2012: 1,810

2011: 1,656

2010: 2,102

2009: 1,903

Value of Narcotics Seized

2016: $698,468

2015: $713,689

2014: $885,211

2013: $1,128,785

2012: $476,025

2011: $1,865,050

2010: $1,177,537

2009: $312,715

Homicides

2016: 31

2015: 23

2014: 22

2013: 21

2012: 14

2011: 13

2010: 17

2009: 20

Robberies

2016: 339

2015: 376

2014: 408

2013: 400

2012: 454

2011: 388

2010: 378

2009: 407

Community interest at heart

When Fowler first started as a police officer in 1989, he’d get out of his patrol car and people would talk about how he didn’t know what it was like to live there. He’d laugh in their face.

“What are you laughing at?” they’d asked

He’d look them square in the eye — “You think I don’t know what it’s like to live down here?”

They wouldn’t respond, realizing the “hood card” couldn’t be played on him.

“When I look at people in the toughest of situations, I always look at them and I think about the Bible verse that says, ‘There by the grace of God go I.’ I can easily see myself in those people’s shoes,” said Fowler, who lives in the city. “As a police officer, and even more so as the chief, to me those are the people that get special attention from me.”

He took the empathy he’d developed directly to the streets doing undercover work for eight and a half years. Those years were the best of his police career, he said.

“It was just like being back out on the streets again,” he said, but without the baggage.

“Some people say life being hard in the hood is an exaggeration. They don’t know what they’re talking about. It’s exhausting to navigate the hood each and every day and all the different dynamics that are associated with it.”

Before climbing the ladder to chief, he was promoted to sergeant and to deputy chief of the Community Services Bureau. It was there where he oversaw the police force’s relationship with the community.

“Every step that he’s taken with Syracuse police, right up to the rank of chief of police, he’s never forgotten that connection with the community,” said Syracuse University Chief Law Enforcement Officer Tony Callisto, who took over as the university chief of public safety when Fowler was with the Community Services Bureau. “He was ahead of his time when it comes to understanding the needs of the community and community policing, and he’s the real deal. The focus on the community is and always has been what makes Frank Fowler an outstanding police officer and police chief.”

He still carries those communication skills, frequently talking to community members who want his ear. Before boarding his flight to St. Louis for the trip home this spring, Fowler took a minute to talk to a man who recognized him. Outside one of his childhood apartments in Kinloch, he chatted up two women who worked at a church across the street. Fowler has addressed concerned SU parents, too.

Said Steve Thompson, a former police chief who now chairs the public safety committee on the Common Council: “He’s got the community interest at heart.”

Victims on the outside

Fowler still remembers responding to the scene of a shooting as a deputy chief, shocked to see what was happening. A woman lay on the sidewalk, weeping. No one paid attention, stepping over her to continue their work.

“There are victims on the outside of the crime tape too,” Fowler says now.

Fowler helped create the Trauma Response Team, a group of people dispatched to scenes of violent crimes, specifically shootings, to help people who aren’t direct victims of the incidents. For Fowler, seeing people grieve at the scene of a shooting hits home.

He got out of school in St. Louis one day and walked out with some friends, including “Toby,” one of his best friends with a large afro. Fowler forgot something in his locker so he ran back inside the school. He got back to the top of the steps when he heard screaming coming from the street corner and saw people standing in a circle.

“That afro was missing,” he said. “My heart just went into my throat.”

Fowler could tell, he said, that the loudest scream was coming from Toby’s sister. He pushed through the circle of teenagers to see his best friend dead on the ground “with half his face missing,” shot at point-blank with a shotgun.

“That’s St. Louis,” Fowler said.

The killing remains unsolved.

“The retirement for me means that I will no longer be the chief of police. It doesn’t mean I’ll no longer work.”

Blue bloods

In a small apartment in St. Louis, a large group of Fowler’s extended family gathered to welcome the chief on his spring trip home. Children played and danced in the backyard while inside, surrounded by family pictures, the adults caught up.

Just before supper, Fowler’s oldest brother, Willie Knox, gathered everyone inside to pray.

“We thank you for blessing the police and those who sacrifice for us and allowing them to go home and spend time with their family, Lord,” Knox said.

Pictures of Fowler hang in his brother’s house, with Fowler’s swearing-in ceremony as chief and a visit to the White House prominent among them.

“We’re all so proud of him,” Knox said.

Fowler will have more time to spend with his family after he retires at the end of the year, the end to a long career in law enforcement. He’ll have more time to watch his favorite TV show, “Blue Bloods,” a CBS show on a family of police officers. His nighttime reading — on an iPad rather than hard copy — will be more peaceful. A trip to Hawaii, something he never got with the Army, is on his retirement bucket list.

Chief Fowler hugs his cousin during a family gathering at the home of his older brother Knox, who was the first in the family to move to St. Louis.

Chief Fowler, who is the youngest of 11 children, is photographed with various sisters and cousins along with his oldest living aunt.

Chief Frank Fowler jokes with his sisters during a family gathering at the home of his older brother Knox, who was the first in the family to move St. Louis.

****

Fowler stands behind a barrier near the Carrier Dome floor. He’s not in a police uniform or suit and tie, his two most frequent outfits. Instead he’s donned a Syracuse hat and jeans, a father in the Dome one October day to support his daughter, a backup on the women’s basketball team.

SU Chief Facilities Officer Pete Sala walks by. The two shake hands. Fowler returns to his secluded spot before SU women’s basketball head coach Quentin Hillsman walks by. The two hug.

As players are introduced to a cheering Dome crowd at Orange Madness, Fowler wanders over near a raised stage where he knows his daughter, Brandi, will be. Her name is announced and Fowler captures his youngest child, who wants to be an FBI agent, dancing on video.

The scrimmage finishes and Fowler walks into the backcourt to leave. He doesn’t get far, though, before stopping to pose for a picture.

The chief’s always willing to engage with the community.

LINKS TO OTHER RESOURCES:

- USA TODAY timeline of the Michael Brown shooting and aftermath

- Syracuse.com video of the Father’s Day shooting aftermath as Chief Frank Fowler and others try to calm the crowd

- Watch enhanced/narrated video of the Father’s Day shooting

Ferguson police Chief Delrish Moss and Syracuse Police Chief Frank Fowler meet for the first time and speak about Moss's first year as Ferguson's chief.

With a new chief in place, Ferguson police force looks to change perception

It’s been about three years since unarmed Michael Brown was fatally shot, and now a black cop from Miami steps up here, with his own experiences as a young black man still fresh in mind

written by:

Justin Mattingly

photography by:

Michael Santiago

FERGUSON, Mo. — Delrish Moss couldn't get the question out of his head.

Ferguson was looking for a police chief, and when a major casually asked the group of Miami cops who would apply, the room laughed. Nobody wanted to go into a situation where police-community relations were on thin ice after the dramatic police shooting of Michael Brown sparked riots and heavy media coverage.

Two days later, the born-and-raised Miami native went to the parking garage to leave after work only to find himself back in his office a few minutes later filling out the application for the job.

“I watched what happened with the riots and all those things,” Moss said in an April interview here. “As I’m looking at that I kept thinking back to the ’80s when we had all the riots in Miami. That’s not good.”

He found himself among the finalists for the job even though he’d never served as a police chief — his highest rank being major. Then one morning he woke up to a deluge of phone calls and text messages. Reporters called from as far as England seeking confirmation from the new chief. The one problem: He hadn’t been told he got the job yet.

The March 2016 announcement came a few hours earlier than initially planned. Ferguson, less than two years after a police shooting that made international headlines and shook a community to its core, had a black police chief. He’s come in and worked to change the perception of the Ferguson police department, making it more community-oriented while putting an increased focus on the city’s officers — both in their mental health and in recruiting.

Moss, 53, had no intention of ever becoming a police officer. Growing up in Miami, he dreamed of being a musician — a trumpet player with a love for jazz.

He was sitting at a bus stop one day in 1978 when a Miami police officer approached the high-schooler and asked where he was going. To work, Moss said.

“Well n***as don’t walk downtown after dark when I’m working,” Moss remembers the officer saying.

“Well n**ers don’t walk downtown after dark when I’m working.” Delrish Moss remembers vividly being told this by a police officer in the '70's. It's one of the encounters with the police he credits with inspiring him to become an officer and make changes from the inside. In 2016, after retiring from the Miami Police Department after 32 years, he was selected to become the new Chief of Police in Ferguson, MO. He was named to the helm after the former chief, Tom Jackson, resigned due to a Justice Department report that cited racial bias in Ferguson's criminal justice system.

The officer searched Moss’ bag before driving off in his patrol car.

A year later Moss was walking down a Miami street when another officer pushed him against a wall and frisked him without saying a word, then left.

“I said ‘Man, I need to become a police officer,’” Moss said this April. “Because if this is the service we’re getting, I’ve got to get us better service than this.”

Over the course of his 32 years with the Miami Police Department, Moss emphasized community relations. He became a spokesman and community liaison for the department in 1996 and when he retired from Miami to go to Ferguson, he was the head of the community relations section of the force.

He spent time patrolling predominantly black Miami neighborhoods and has used those Miami experiences to influence his management style.

“To be a black and be a police officer is to live inside and outside of two worlds,” he said. “Black people don’t see you all the time as black because you’re a police officer. They see you as blue.”

Moss’ experience, specifically in community engagement, made him stand out among the 50-plus Ferguson applicants, said De’Carlon Seewood, city manager at the time.

“We understand the past 18 months have not been easy for everyone, but the city is now moving forward and we are excited to have Major Moss lead our police department,” Mayor James Knowles III, who was re-elected in April, said in a statement at the time of Moss’ hiring.

Moss started in the city of 21,000 in May 2016, about a year after the previous chief, Thomas Jackson, resigned in March 2015. There were still protests from the shooting of the unarmed black teenager, Brown, in August 2014. The population was 67 percent black with a police force that was about 2 percent.

After the Brown shooting, thousands of community members — some from Ferguson, others from outside — took to the streets to protest the shooting. The story quickly made international news as protests turned violent, with Molotov cocktails thrown at police, who fired tear gas and rubber bullets while bringing in military-style vehicles.

A jury decided not to charge Officer Darren Wilson, a white officer, over the killing in November 2014. Protests following the jury’s decision spread from Ferguson to across the U.S.

The Department of Justice investigated the shooting and the Ferguson Police Department. The DOJ outlined discriminatory police practices against the black community, including a disproportionate 93 percent of arrests despite comprising 67 percent of the population. In the Mike Brown report, the DOJ concluded that there was no evidence showing Wilson, who shot Brown, used unreasonable force.

Harry Dilworth, a 24-year veteran of the Ferguson Police Department, described the aftermath of the Brown shooting as horrible and stressful. As one of the few black officers on the force, he had to deal with being called a “sellout” and an “Uncle Tom,” according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Driving through a residential neighborhood in the city on a quiet afternoon this spring, Dilworth, wearing a “Blue Lives Matter” bracelet, spoke softly as he described the “real Ferguson.” Those neighborhoods, with children playing in the yard and people walking on the street, were “held hostage” during the 2014 riots, he said.

Ferguson police officers have initiated fewer stops since the shooting in fear of confrontation, he said.

“We became more reactive than proactive because we didn’t want to be the next person on a YouTube video,” Dilworth said.

“We became more reactive than proactive because we didn’t want to be the next person on a YouTube video,” Dilworth said.

Along Canfield Drive, where Brown was shot, residents of nearby apartments eyed the police patrol car for a few seconds as it drove by. In the middle of the road: a dark patch of pavement where Brown was stretched for four hours. On the sidewalk: a plaque that pays tribute to the 18-year-old.

In his first year on the job, Moss has tried to connect with the divided community. He’s held community forums and visited people door-to-door. He’s tried to advance a community policing strategy where officers engage with the community more while also getting officers into schools.

Personnel is stretched thin, however. At its height the Ferguson Police Department had 55 officers. There are currently 38 officers on the force, with Moss looking to add 16 more. Despite community pressure to hire more officers faster, Moss is taking his time with the process.

He saw the 1980 Miami riots unfold outside his own house, confrontations that left 18 people dead. The Miami force went from 900 officers at the time of the riots to 400 before rocketing up to 1,200 as the department took shortcuts to add personnel.

“We’re not going to circumvent any part of our system to bring people on,” Moss said, adding that he’s working to recruit officers who better represent the community they’d be patrolling.

Once those officers are hired, Moss wants them to have the help they need personally. Moss is seeking a 100 percent “Blue Courage” rate for his department, a program where officers take part in a self-reflection workshop fashioned to make them better.

Moss went to Ferguson with a plan to change things for a small community now in the international spotlight.

“It takes time to turn the culture of a department around. I think most police chiefs, your best hope is to plant good seeds,” Moss said. “Whatever we do — because the world is watching — will have some bearing on what happens elsewhere.”

Moss knows there will still be people in the community who don’t like police no matter the changes he makes. He jokes that there are people who love him as a person, but not as a police chief.

“You have to just remember what your purpose is and do the best you can,” he said. “Execute your plan and keep moving forward. It’s not personal.”

Ferguson police Chief Delrish Moss and Syracuse Police Chief Frank Fowler meet for the first time and speak about Moss's first year as Ferguson's chief.

Ferguson police Chief Delrish Moss and Syracuse Police Chief Frank Fowler meet for the first time and speak about Moss's first year as Ferguson's chief.