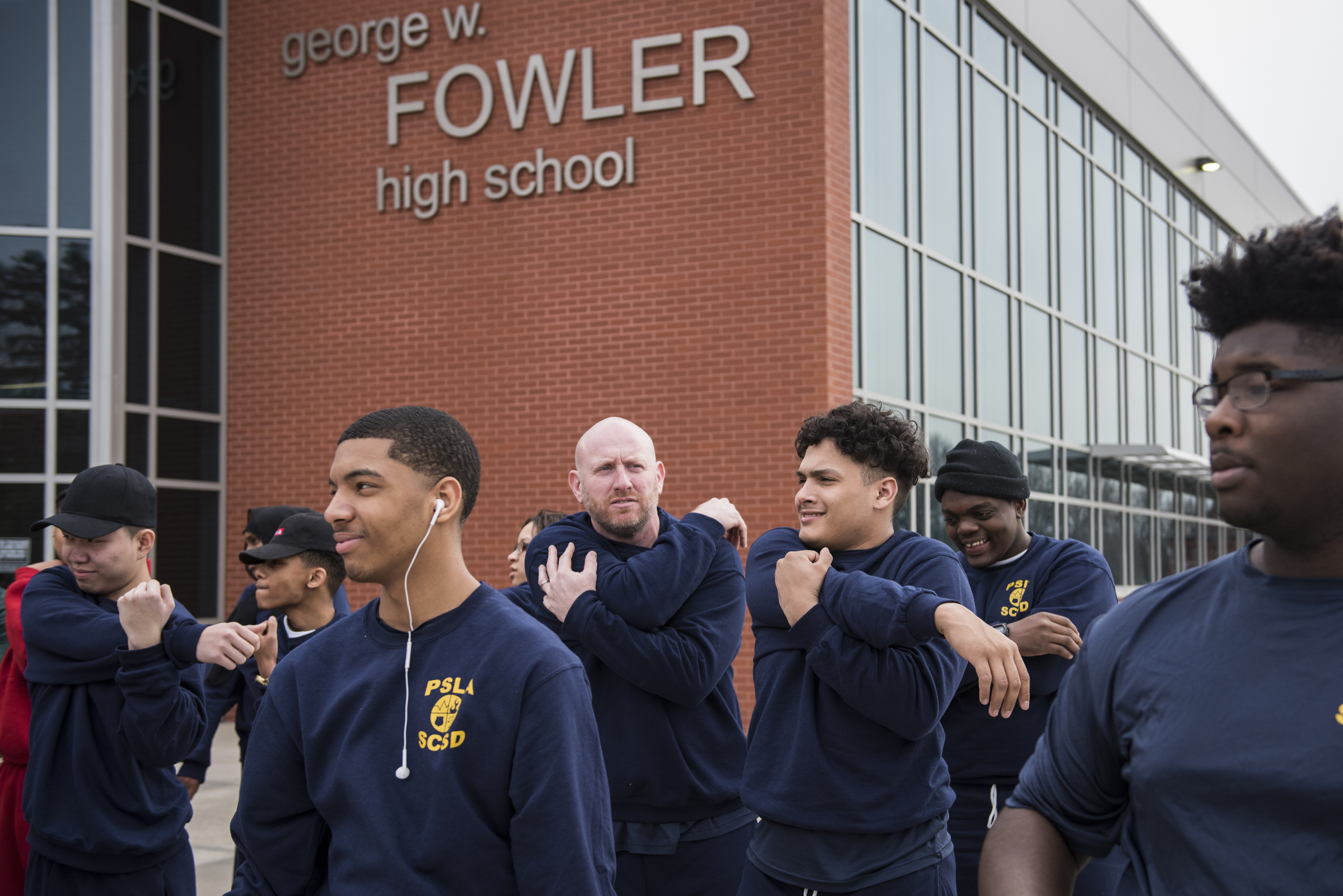

John Correa and his peers stand in attention during PT training. The physical fitness exam to become a police offer requires certain standards, including those under the age 29 must be able to run 1.5 miles under 12 minutes and 38 seconds.

Teen dreams: For these 16, it starts now with a high school law-enforcement track

Their teacher hopes it preps them well, while improving their friends' image of police

written by:

Max Jakubowski

photography by:

Bryan Cerejio

ALSO FIND:

> The 10 other PSLA career paths

> What high schoolers think of the SPD

Strumming a guitar inside his friend’s home on a spring evening, Ehblue Htoo paused and looked up.

“Don’t we need a bass player for Sunday’s service?” he asks his friends and pastor during a weekly youth worship group meeting.

His pastor nods and Ehblue, known as “Blu” to his friends, confirms he’ll play bass on Sunday.

The Syracuse high school student, originally from Thailand and no more than 5-foot-6 and 110 pounds, has always found music as an avenue of happiness. While music and his service at his church is a mainstay in his life, “Blu” does have an ultimate career goal.

To become a cop.

****

John Correa works 17 hours a week at a local grocery store to help support his family. When he’s not working, he can be found at the gym, meticulously practicing his jump shot in pursuit of basketball dreams.

“I’m constantly trying to get better,” Correa says.

However, in a few years Correa might not be lacing up Nike basketball shoes, but instead fitting into a pair of police duty boots.

He too wants to become a cop.

****

The extraordinary goal they each share is being shaped within the halls of a city school building.

****

Htoo (pronounced “too”) and Correa are part of a 16-student junior class in the law enforcement track at the Public Service Leadership Academy, a career and technical school at Fowler High School. PSLA offers four different “academies” with a total of 10 pathways for students to choose from, including law enforcement.

The class prepares students for a career in law enforcement, including the possibility of becoming a police officer.

In 2014, the Syracuse school board voted to replace Fowler with PSLA. The two schools have shared the same building since 2014, with the final graduating senior class of Fowler set for 2017 before PSLA is the only remaining school.

“Prior to freshman year, I was planning to go to Henninger (High School) but was assigned to PSLA,” Htoo explained. “I really tried to transfer to Henninger,” he recalled with a grin.

When a school district representative called him and told him about the new PSLA program and listed the different pathways, law enforcement caught Htoo’s attention.

But his friends were skeptical.

“They said you are Asian and too small,” Htoo recalled.

His teacher, retired Army military police Maj. Jamie Bazdaric, joined PSLA as a law enforcement instructor in March 2016 and is now the full-time director of the law enforcement track.

As part of the first responder academy, Bazdaric, or as his students call him, “Major B,” prepares his students for a life of service and sacrifice, especially if they want to become police officers.

“They have to be dedicated and understand what they are committing themselves to,” Bazdaric said.

He describes the law enforcement track as a “great vehicle” to become employable, but more importantly, get his students to graduate.

As part of the law enforcement curriculum, Bazdaric helps his students achieve five industry-level certifications and 10 credit hours toward college criminal justice courses. In addition, students are exposed to agencies in the area, including the district attorney’s office, Syracuse Police Department and Onondaga County Sheriff’s Office. These agencies all offer internship programs during and after high school.

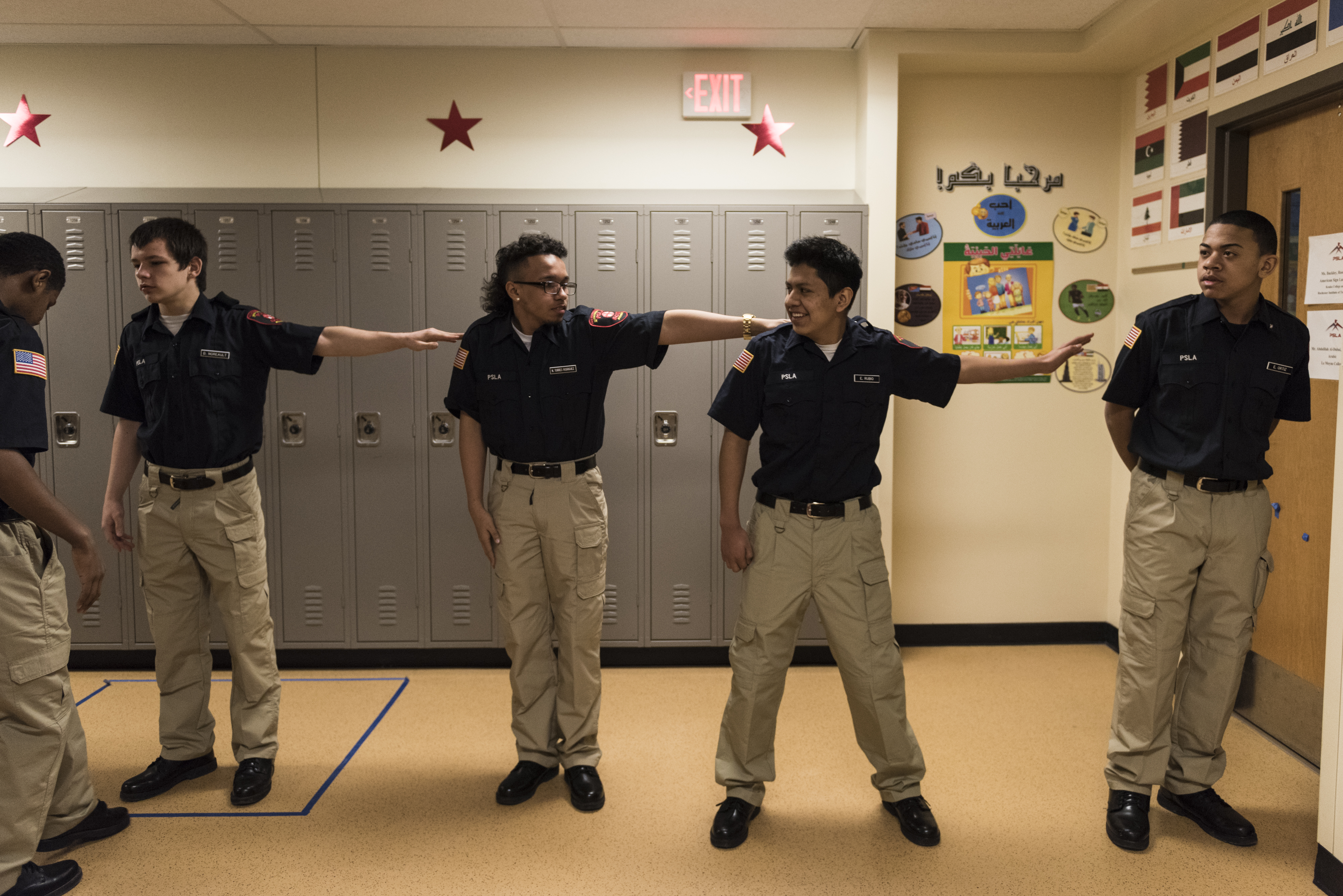

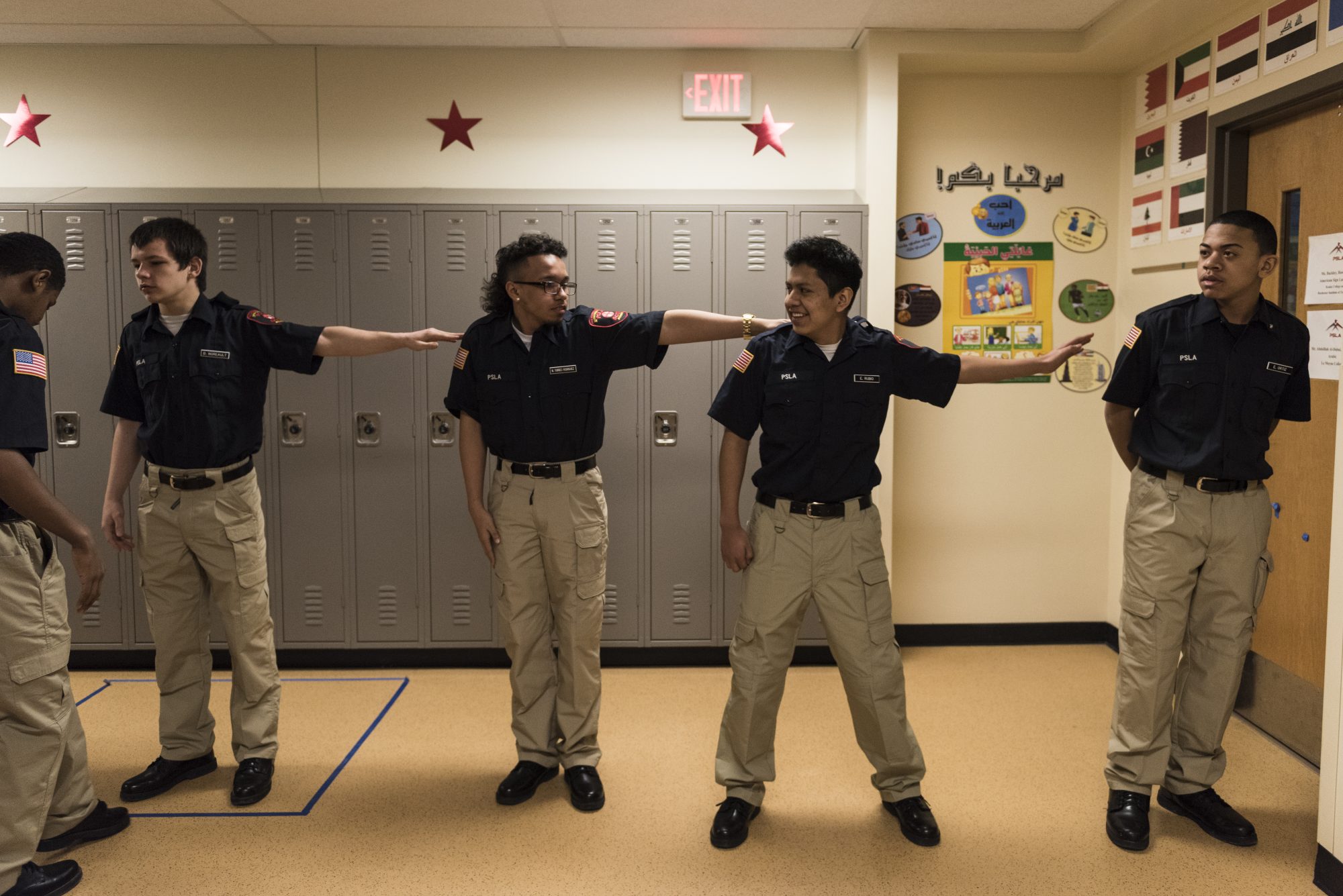

Uniform inspections and workouts are also major points of emphasis in the curriculum, with PT training every week. Some specific lessons include handcuff techniques and use-of-force training sessions.

“Kids come here and they want to be cops and learn the fun stuff, but anyone in law enforcement will tell you physical training and uniform preparedness are key elements,” Bazdaric said.

Bazdaric also helps work on the image of the police not only in his class, but through the entire school. In some instances, the class will run drills through hallways or use radios throughout the school day with their police uniforms. Bazdaric wants the rest of PSLA to see how their classmates are working hard to become cops, but are still friendly and cordial with everyone. He says this goes a long way to projecting a high-quality image of police by others moving forward.

When talking to prospective eighth-graders interested in the law enforcement pathway, Bazdaric centers his “pitch” around three points: certification, college and community.

He tries to sell parents on those three objectives, saying their kids will pass certifications to help with future employment, earn college credit and also go through high school in a firm, yet caring atmosphere.

The recruiting pitch seems to be working. The current freshman class has 15 students, up from the 11 in the sophomore class. Bazdaric expects next year’s incoming class to be in the high teens as well.

Bazdaric has not had many parents tell him that they are worried about their son or daughter training to become a cop. Instead, many parents are supportive and believe that disciplined training is good for their children in the long haul.

Correa, of Puerto Rican descent, hails from the east side of town, and says his mother, uncle and grandmother have supported his decision to be a cop since Day One.

“(They’ve) given me all the support there is,” Correa said.

Entering the track, Correa was not the biggest fan of the police in general, but after learning the history of police and basic training in the law-enforcement class, he started to think more like a cop.

“This course is building me up to become a leader and a police officer at the same time,” Correa explained.

In March 2017, the class suffered a tragedy, when classmate Kevin LaShomb died suddenly. LaShomb was Correa’s best friend; Correa credited him as one reason for joining the law enforcement pathway.

“We had to become closer to go through that,” Correa said of how the law enforcement class dealt with LaShomb’s death. “You can’t go through that alone and now we are a really tight pack.”

Bazdaric credited both Htoo and Correa for stepping up to help keep the class together during that difficult time.

“The biggest growth experience hasn’t been a test, it’s been the loss of a classmate,” Bazdaric said.

Besides training and studying, the class discusses local policing matters. A Father’s Day shooting back in June 2016, which left one man dead from officer fire, caused a lot of conversation in the greater Syracuse area. An SPD officer shot and killed a man who had pulled a gun. A grand jury later found the officer justified for firing. Outside of class, Correa said that incident was the only time he’s heard family and friends speak differently about SPD.

“They would say the scenario was wrong and messed up, but I protected the SPD, saying they were doing their job,” he said.

Htoo agreed, saying SPD is just performing its duties: to protect the community.

“They are human, too. They want to get home to their family. What they do is necessary.”

Major Jamie Bazdaric talks to a student before the start of physical fitness training. Major B, has structured the curriculum in a way that prepares students for the law enforcement career field.

PSLA Fowler law enforcement students begin to warmup for PT outside.

John Correa, right, runs with his law enforcement peers. While these students train for the requirements of the police academy and obtain various certifications, they cannot immediately apply to become police officers because many are not of age. They must first go to college or work different jobs after graduating high school.

PSLA Law Enforcement student Wilburt Reddick places a radio on student Tyler Patterson. Camaraderie is something that is also taught in the program.

School offers 10 career "pathways" for students

At the Public Service Leadership Academy, high school students can choose between four different academies. Students spend their freshman year attending classes from all of the pathways before committing to one for the remainder of high school. The four academies and their pathways:

First Responder Academy

Law Enforcement

Fire Rescue

Emergency Medical Technical

Forensic Science/Crime Scene Investigations

Homeland Security Academy

Computer Forensic

Cybersecurity

Geospatial Intelligence

Military Science Academy

Navy JROTC

Entrepreneurial Academy

Cosmetology/Barbering

Electrical Trades

Major B runs through the school's hallways with his students during PT training. Everytime the students run, they cheer in cadence. On this day, while many teachers went into the hallway to cheer on the students, others weren't too happy with the noise. "It's what gets the kids excited," says Major B about the chants.

Bazdaric believes the opportunity to make a difference and see diversity in police is what drives all of his students, specifically Htoo and Correa. In 2016, SPD had only 10.5 percent, or 47 out of 445 sworn officers, identify as a minority. That is below the national average of 27 percent.

“The desire to go into a track that gives them the ability to make a change or be a part of something and make a difference,” he said about why kids would want go on this track in high school.

Bazdaric also has witnessed perspectives to police change not in only in his class, but also in the school.

“The change they (his students) are making is already happening here at this school,” he added.

Samjana Thapa, a junior computer forensics student at PSLA, says she and the rest of the student body have noticed the impact the law enforcement class has on the school. “They always seem so focused when they wear their uniforms and practice running in the hallways,” she said. “I think they all want to be cops to be able to do good things for the community.”

“They always seem so focused when they wear their uniforms and practice running in the hallways,” she said. “I think they all want to be cops to be able to do good things for the community.”

According to Bazdaric, Fowler/PSLA has gone from one of the lowest-performing high schools in the state academically, to now the type of school that is getting attendance awards and a higher graduation rate.

Bazdaric believes both Htoo and Correa have incredible potential.

“John is intelligent and personable,” he said. “He has an ability to lead and he wants to learn. Ehblue is a high honor roll student and a classroom leader.”

Bazdaric plans to recommend Htoo for the district attorney’s office internship program next year.

Htoo is grateful for the relationships and connections Bazdaric and PSLA have provided him, especially the police career connections he has already made.

For Correa, this class has been about motivating himself to attain his aspiration of becoming a police officer.

“The integrity and will to keep moving forward,” he said about what he will take away from this class. “You need that ending fire to keep going and complete what you want to.”

Major B currently teaches juniors, sophomores and freshman as the PSLA program is only three years old. Here, his sophomore class learns about lining up for uniform inspections, which they are expected to wear each Tuesday.

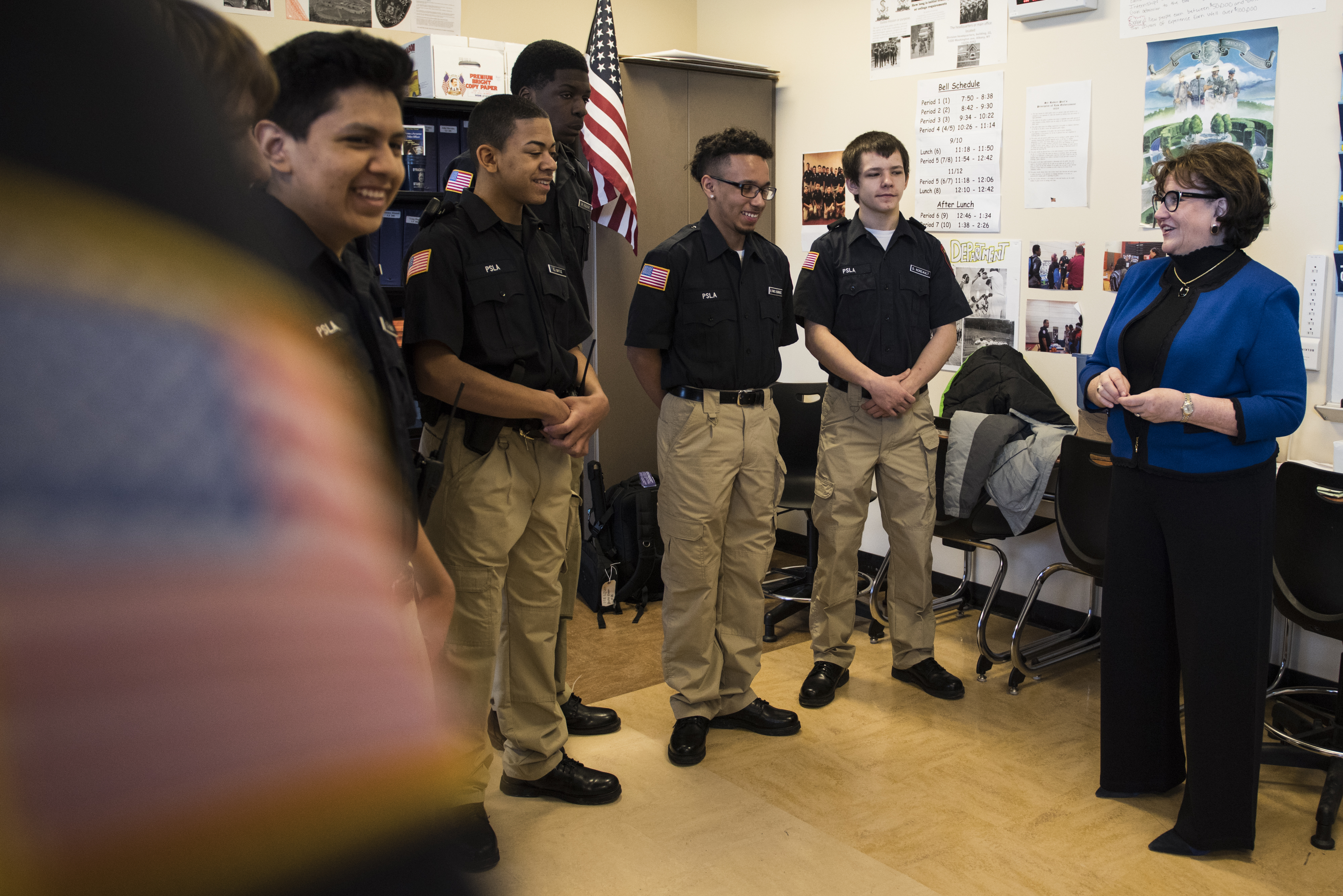

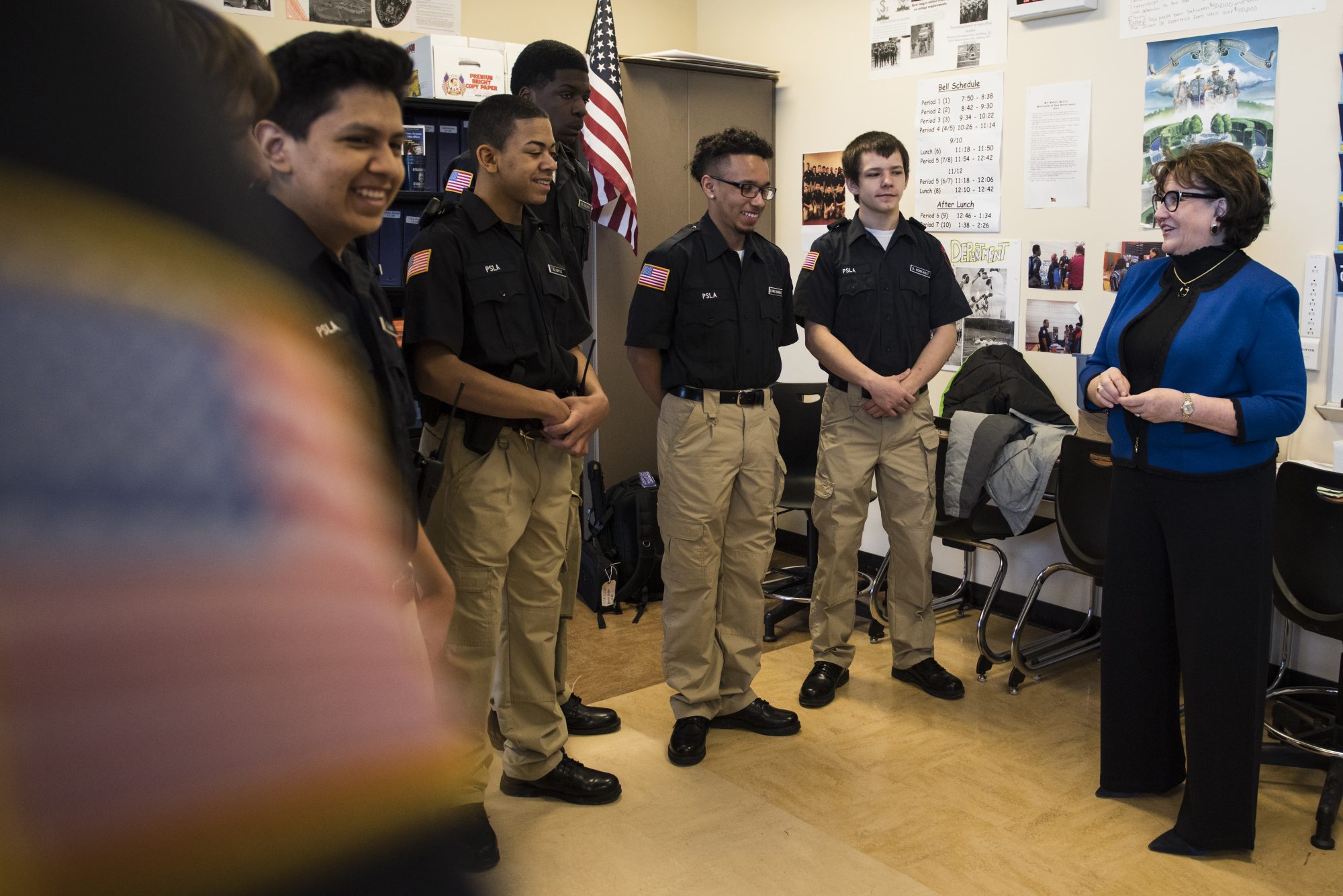

New York State Commissioner of Education, MaryEllen Elia, talks to the law enforcement class at PSLA Fowler. Elia was on a school visit to see the various programs PSLA Fowler now offers.

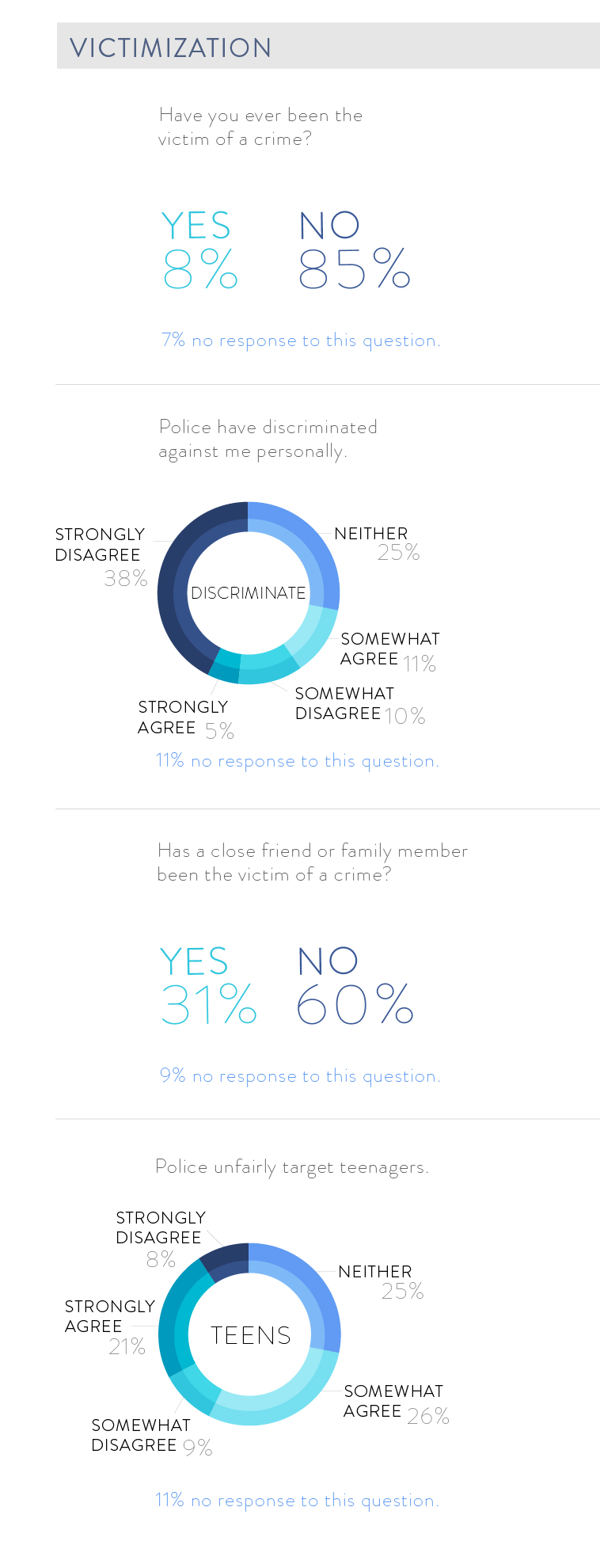

Survey shows students' view of police changes at the schoolhouse doors

Most get to know officers at school, but on the streets minorities, especially, are less trusting

written by:

E.Jay Zarett

photography by:

Bryan Cerejio

IN THIS ARTICLE

> Community Police Survey

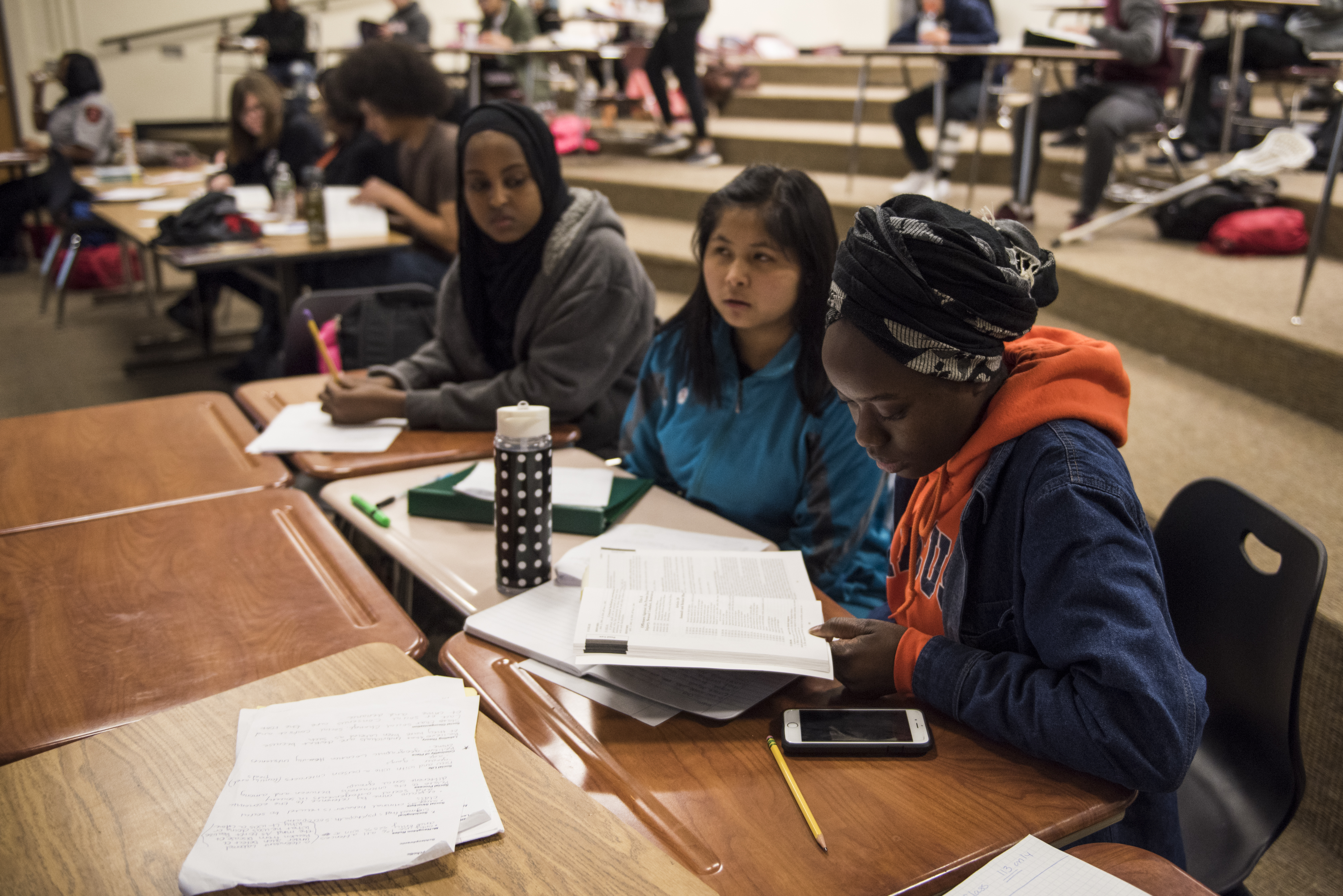

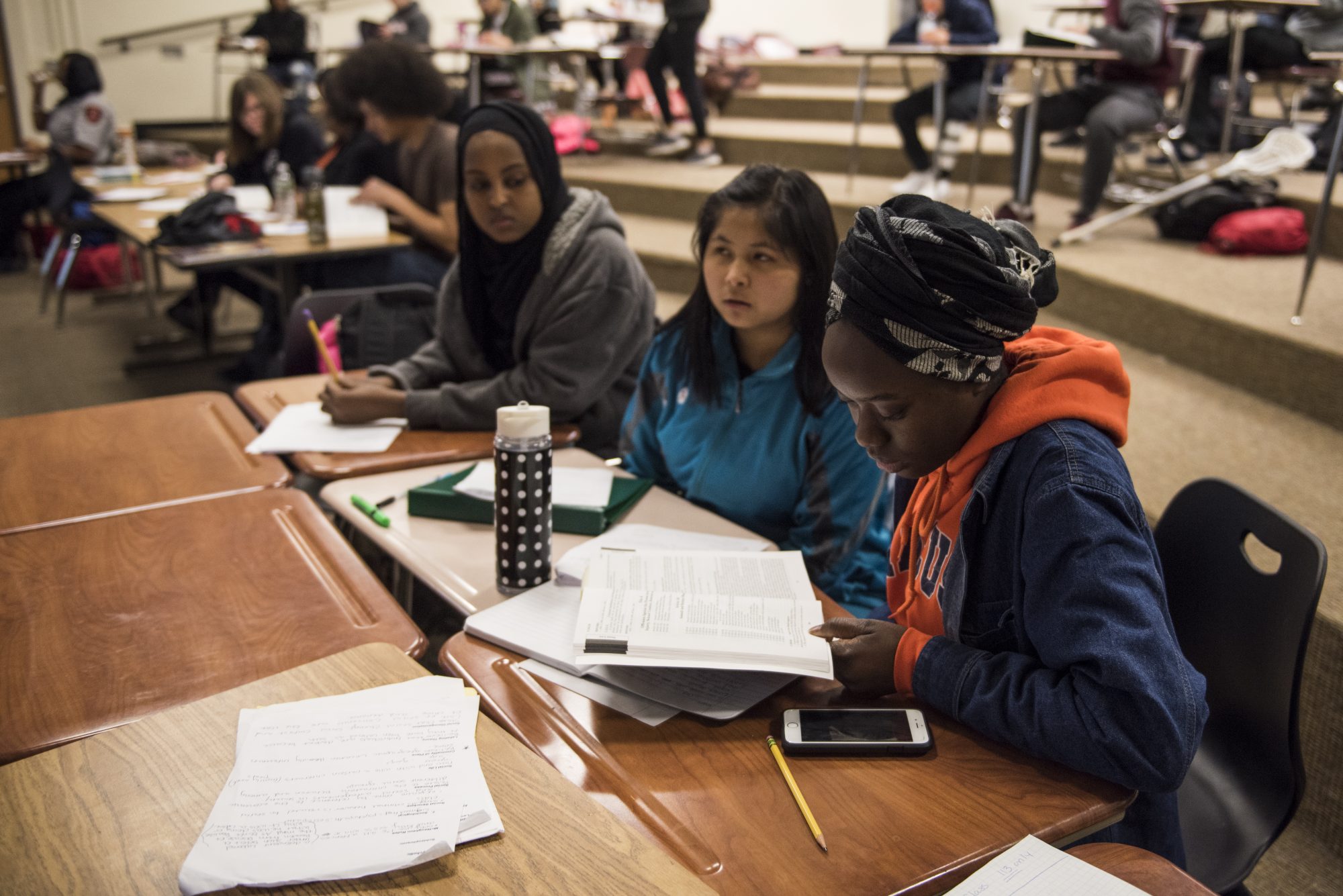

Syracuse city students tend to have positive interactions with police officers stationed in their schools, according to a recent survey conducted by the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. But the survey found that those attitudes change when teens deal with officers outside of that setting.

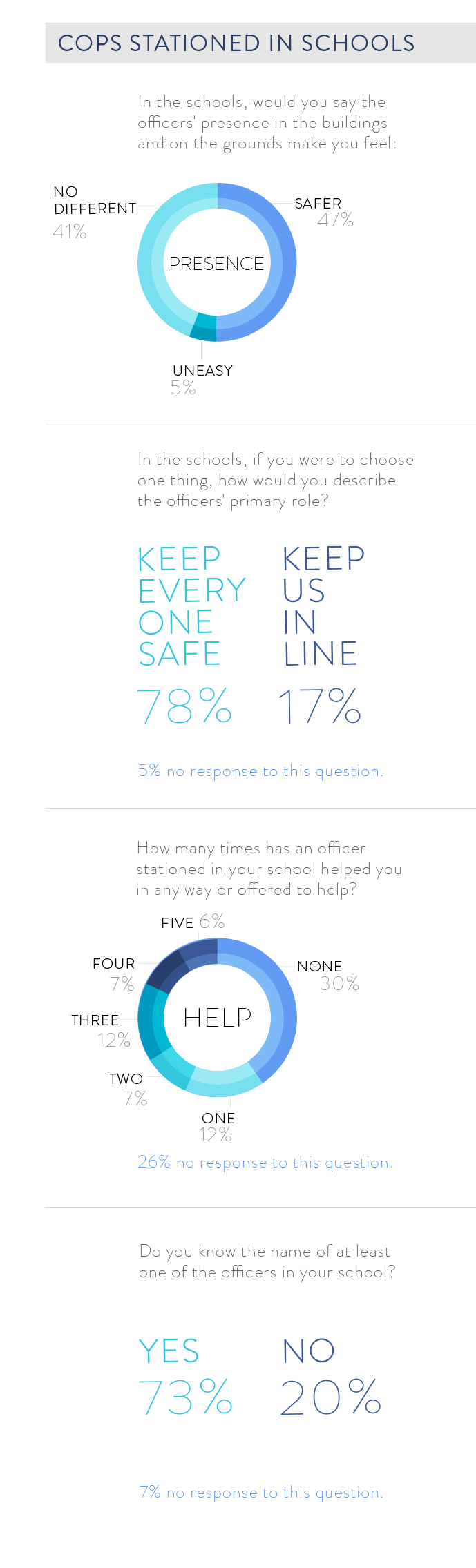

The survey also found that black, Latino and Asian respondents were more likely than white students to agree with the statement that police unfairly target minorities

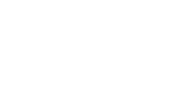

The survey asked respondents 40 questions in all about their interactions and experiences with police officers and law enforcement. A total of 184 students from four different high schools in the Syracuse City School District completed the survey in their government classes.

The survey results can't be said to represent the views and experiences of all Syracuse students for certain, but they do offer reasonably accurate insight into the experiences of many of them.

Ninety-five percent of respondents were seniors and 86 percent were older than 17. Fifty-two percent of those who took the survey identify as black, 15 percent as white, and just over 10 percent each as Latino or Asian.

As a whole, the city of Syracuse population is about 55 percent white, 29 percent black, 8 percent Latino and 7 percent Asian, according to the 2015 American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau.

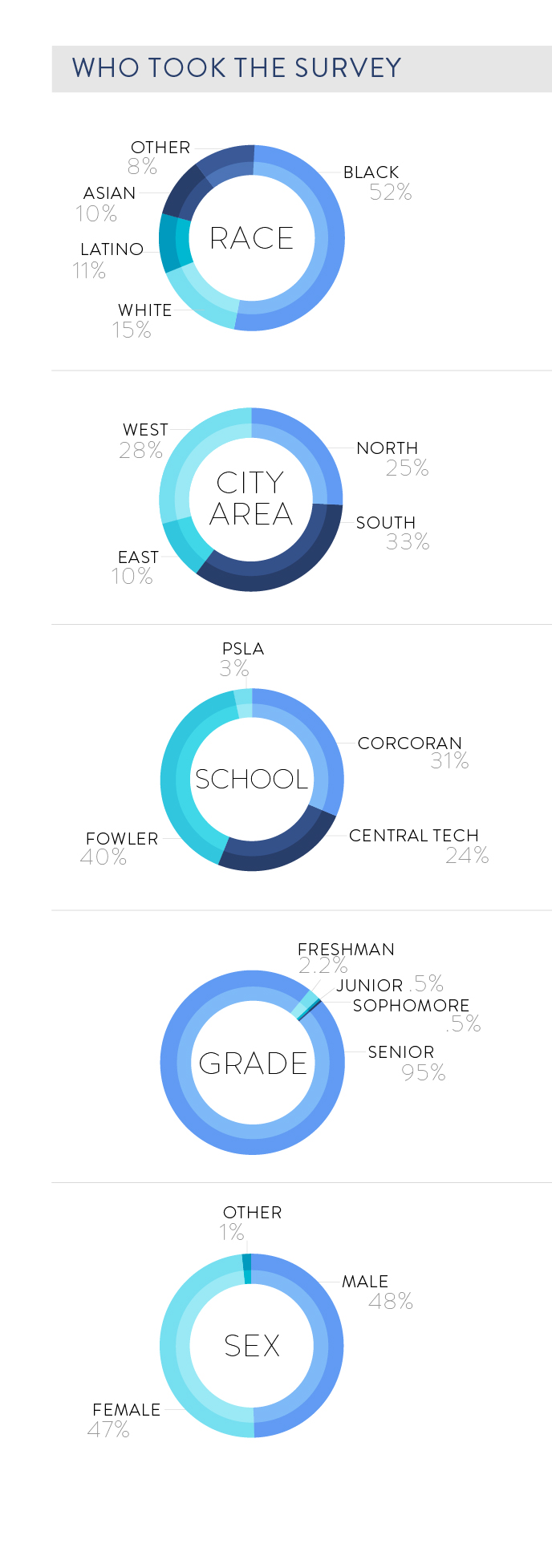

Students were asked 13 questions relating specifically to their interactions with officers assigned to their high schools by the Syracuse Police Department — known as resource officers.

Just 5 percent of respondents said that the officers’ presence on school grounds made them feel uneasy, compared with 48 percent who said that the officers made them feel safer.

“The police in our school are kind,” a 19-year-old female from Corcoran High School said in the survey. “They do everything they can to keep us safe and in a good mood.”

Almost three-quarters of respondents said that they knew the name of at least one officer who worked in their school and 94 percent responded that an officer had helped, or offered to help, with a problem that had arisen. Ninety-five percent of students said that an officer had engaged them in a personal conversation on at least one occasion.

“The police in my school are very good people,” one 18-year-old female Corcoran High School senior wrote in the survey. “They don't always try to be aggressive but they try to make us as safe as possible. They do their jobs!”

Anthony Davis, the Syracuse City School District’s assistant superintendent for high schools and career tech education, said that the number of resource officers stationed at each school varies by student enrollment. Davis estimated that two officers and six to eight school sentries —monitors responsible for patrolling the hallways— are on duty at one time in Henninger High School, Syracuse’s largest with 1,745 students. In total, 19,951 students are enrolled in the Syracuse City School District, according to the New York State Education Department.

Davis said that he was not surprised by the students’ positive responses regarding resource officers.

“They are doing some of the preventive measures that will keep kids from getting into a situation where something is illegal,” Davis said. “I think in that sense they may be seen as a positive resource versus someone who is constantly after them for something that they’ve done wrong.”

Delores Jones-Brown, the founding director of John Jay College’s Center on Race, Crime and Justice, has conducted extensive research on police-community relations and juvenile justice. She said that students become more trusting of police officers when they begin to know them on a personal level.

“(I’ve found that) the symbolic police officer is something that young people might not care for,” Jones-Brown said. “But, when they have an opportunity to interact with the police on a non-intrusive basis, they can see that the individual police officers are OK.”

Student responses changed when they were asked about their feelings toward — and interactions with — police officers outside of school.

Davis said that this shift in attitude was most likely caused by the environment in which students deal with the officers.

“Once you’re in a school, the officer isn’t the primary source,” Davis said. “They are not directly in charge. They only take over if the building asks them to, or if they see something illegal. So, they have means to create relationships. On the street, once they are called, they’re in total control from that moment. I think they come in with a different attitude, one of self-preservation that nothing happens to them.

“I’m not saying that the situations that the officers have to deal with are always easy or simple. These things are very complicated. But, I think our kids are simplifying it, and they feel like there is wrongdoing at times and they are internalizing that.”

Just 36 percent of all respondents said that they somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement “I trust the police.”

That number shrank to just 29 percent of students who identified as black or Latino, while 58 percent of white respondents and 63 percent of Asian respondents somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement.

“I've had almost no direct contact with police,” a female 17-year-old senior at the Institute of Technology at Syracuse Central said in the survey. “But, I generally do not feel safe around them out of fear that they may assault me.”

Forty-seven percent of students indicated that they somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement that police unfairly target teenagers, and only 30 percent said that they felt as if the police trusted them.

Fifty-nine percent of black, 53 percent of Asian and 52 percent of Latino respondents said that they somewhat or strongly agreed that police unfairly target minorities. Just 25 percent of white students who participated in the survey responded in the same way.

Jones-Brown said that students may feel more positively towards the officers in their schools because of the consistent interactions they have with them.

“Because the officers are encountering the young people on a daily basis, there’s not that fear based on the unknown,” Jones-Brown said. “Too often (officers) are being trained to think that they are going to be under attack. They don’t understand that when they start out in an agitated state, then it agitates the civilian. I think that the familiarity that the (resource officers) have with the students reduces stereotypes, specifically negative stereotypes, and reduces the level of fear that would be involved in interacting with a young person.”

Forty-seven percent of respondents said that they had been a passenger in a car that was pulled over by the police, while nine percent said that they had been the driver of a vehicle that was stopped.

Two-thirds of students, however, responded that they had never spoken with a parent or other adult about what to do in that situation or if they are approached by an officer on the street.

John Klofas, a professor of criminal justice at the Rochester Institute of Technology and director of The Center for Public Safety Initiatives, said that he would have expected more students to have had this conversation with an adult or authority figure.

“These concerns in many ways are very prevalent in the minds of young people and presumably the minds of parents,” Klofas said. “Over the years I’ve spent a lot of time talking to people about this very issue.”

Davis said that this could be because many students in the district rely on peers as their main source of information.

“I don’t know if our kids today are conscious in having those conversations,” Davis said. “I think the anger and perceptions are so deeply woven into their experiences that to have those conversations would be difficult for them. I think they don’t know how to handle their emotions, so therefore you don’t talk about it and I think that is extremely problematic.”

Some additional student comments in the survey:

- “I have never had an interaction with the police, but I have seen them treat others sometimes in a good way and sometimes in a bad way.” – 18-year-old, white, female, senior at Corcoran High School

- “I've had police that were off-duty stop and help us off of the highway when our vehicle ran out of gas, and police have driven me and my friend home when the buses stopped running.” – 16-year-old, black, female, senior at Corcoran High School

- “Over an incident at a family member’s house from what I remember, the officer that came was very, very rude and was cursing — even though everyone was calm and answering questions.” – 18-year-old, race unidentified, female, senior at Fowler High School

- “Nice, friendly, not rude like everyone else says they are.” — 17-year-old, white, female, senior at Fowler High School

- “Some are nice and some take the situation too far. Fourth of July, police officers came to my neighbors’ house and told them to be quiet and then they were yelling and cussing at us because we were doing fireworks.” —19-year-old, black, female, senior at Fowler High School

- “I've seen the local police help out a lot, but the media sometimes portrays the police asbad guys.” — 18-year-old, Asian, male, senior at Institute of Technology at Syracuse Central